|

Earnings-at-Risk

Short-Term view of IRR

By most definitions, accounting or otherwise, when we

communicate something as short-term, we usually refer to a time frame

of one year or less. When measuring interest rate risk on an earnings

perspective, this same concept applies. Short-term interest rate risk

is measured by initially establishing a one year earnings forecast.

This base forecast assumes that both the level and structure of market

rates of interest are held constant from the last historical period.

The balance sheet, in terms of overall size and mix, is constructed

using a managerial forecast or a projection.

IRR is a measure of possible loss caused by

interest rate changes. Therefore the model introduces two

instantaneous, parallel "shocks" to the base set of rates (common

practice is to use +/-200bp movements) and then re-computes the

expected earnings. The Earnings-at-Risk is the largest negative change

between the base forecast and one of the "shock" scenarios. The

measure is usually stated as a percentage change of either net

interest income or net income. |

A long-time advisor and former board member of our firm used to be CFO of a

large bank in nearby Baltimore, Maryland. That was back in the 1970’s. He

says, “Back then our Chairman would always ask the same question after I

presented the budget and the projected net interest margin, ‘So what happens

when interest rates go up…or down?”

Bank management teams across the country are still asking the same

question today. Only now we have a name for it, we call it Interest Rate

Risk. We also have better ways to measure and monitor it, thanks to the

increased availability of data and more powerful technology.

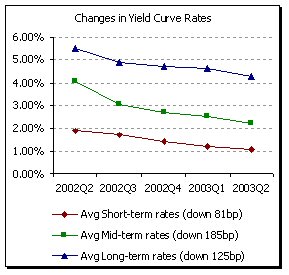

Observing history

Recently it seems like rates have been low for so long, that it’s hard to

imagine a dynamic market rate environment. From June 30, 2002 to June 30,

2003 Fed Funds had only moved down 50bp from 1.75% to 1.25%. However over

the same time frame the treasury yield curve changed quite a bit.

The most significant change occurred in mid-term rates (those rates

between 1 and 10 years). Mid-term rates went from an average of 4.08% down

to 2.22%, a change of over 180bp. Long-term rates moved in a similar

fashion, moving from an average of 5.55% down to 4.30%, a shift down of

125bp. Movements on the short end of the curve were much closer to the

change in fed funds with short-term rates dropping 81bp from 1.89% down to

1.09%. The most significant change occurred in mid-term rates (those rates

between 1 and 10 years). Mid-term rates went from an average of 4.08% down

to 2.22%, a change of over 180bp. Long-term rates moved in a similar

fashion, moving from an average of 5.55% down to 4.30%, a shift down of

125bp. Movements on the short end of the curve were much closer to the

change in fed funds with short-term rates dropping 81bp from 1.89% down to

1.09%.

Margin has suffered

This falling rate environment has taken its toll on the banking industry

over the past four quarters. In fact, the headline in the FDIC’s Quarterly

Banking Profile for March 31, 2003 was “Net Interest Margins Continue to

Narrow” and the headline for June 30, 2003 was “Net Interest Margins Remain

Under Pressure.”

In March 2003 the FDIC reported that “the average net interest margin…was

3.80 percent, 26 basis points lower than a year earlier. Among institutions

with less than $100 million in assets…the average net interest margin has

fallen by 7 basis points in the last four quarters; at larger institutions,

the margin decline over this period has averaged 27 basis points.”

This downward pressure continued into June for larger banks. The average

margin fell from 3.79 down to 3.72. The FDIC also reported that, “more than

half of all institutions – 51.4% - saw their net interest margin decline in

the second quarter.”

Back to the original question

Given that market rates have fallen and interest margins have suffered,

let us come back to the original question. What will happen to interest

margin if market rates change?

One of the best ways to learn how changing rates will affect net interest

margin is to use an interest rate risk (IRR) model like A/L BENCHMARKS.

Models like this typically measure IRR by examining Net Interest Earnings at

Risk (a.k.a. Margin at Risk, see side bar for an explanation). The goal of

such a process is to predict what percentage changes in margin will occur as

a result of either an increase or a decrease in market interest rates.

Rewind

To help answer the original question, it is helpful to look at some industry

peer information. The A/L BENCHMARKS industry peer database has

Margin-at-Risk information for the industry as far back as 1996.

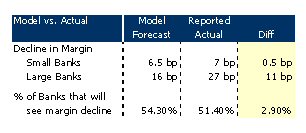

Peer data from one year ago (June 30, 2002) showed that banks with less

than $100 million in total assets had 1.5% of their margin at risk given a

rate shock down. This equates to a decrease of about 6 ½ basis points if

rates fall. Larger banks showed a decrease of 3.9%, or 16 basis points,

given a rate shock down. These numbers seem consistent with the actual

industry performance reported by the FDIC (see table for a comparison). Peer data from one year ago (June 30, 2002) showed that banks with less

than $100 million in total assets had 1.5% of their margin at risk given a

rate shock down. This equates to a decrease of about 6 ½ basis points if

rates fall. Larger banks showed a decrease of 3.9%, or 16 basis points,

given a rate shock down. These numbers seem consistent with the actual

industry performance reported by the FDIC (see table for a comparison).

The FDIC also reported that roughly half (51.4%) of all banks showed a

decline in net interest margin from March 31, 2003 to June 30, 2003. Again

this seems consistent with what the A/L BENCHMARKS peer data predicted last

quarter. The March 31, 2003 peer data showed that 3319 banks out of 6114

(54.3%) were exposed to falling rates. Such results show that the A/L

BENCHMARKS model, and its peer data, can reasonably project what will happen

to a bank’s margin when market rates change.

Look ahead, and prepare

Today, most of the industry believes that market rates will begin to rise

within the next year. However, we are all aware that there is no guarantee.

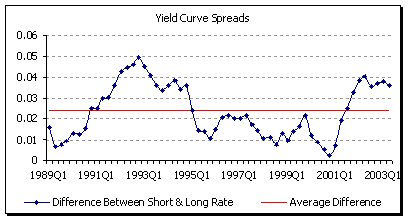

In fact if we look at treasury yield curve data over the past several years,

we find data that might support a rate movement either way.

The graph shows the average spread between the long and short points on

the yield curve from March 1989 until June 2003. The average spread over

that time frame was 2.37%. The spread as of June 2003 was 3.61% down from

3.80% in March. This data might suggest that the curve is still too steep.

If that’s the case long rates must come down (again) or short rates must

rise. On the other hand, perhaps this data only tells us what we already

know, that market interest rates will change. The graph shows the average spread between the long and short points on

the yield curve from March 1989 until June 2003. The average spread over

that time frame was 2.37%. The spread as of June 2003 was 3.61% down from

3.80% in March. This data might suggest that the curve is still too steep.

If that’s the case long rates must come down (again) or short rates must

rise. On the other hand, perhaps this data only tells us what we already

know, that market interest rates will change.

What will happen to your bank’s interest margin when market rates change?

Are you positioned to take advantage of rising rates? The June 30, 2003 peer

data suggests that over 50% of all banks are. The data and tools you need to

manage your margin are available. Is your IRR model accurately telling you

what to anticipate? |